Sermon for the Third Sunday after the Epiphany, preached on Sunday, January 26, 2020, by the Rev. Daniel M. Ulrich.

Sermon for the Third Sunday after the Epiphany, preached on Sunday, January 26, 2020, by the Rev. Daniel M. Ulrich.

From that time Jesus began to preach, saying, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt 4:17).

We’re

obsessed with our bodies, especially how they feel. We focus

on our infirmities. We think about our aches and pains when we get out

of bed. We think about the chronic conditions that plague us. We’re concerned with our

diseases and illnesses. But are we concerned with our true infirmity? Do we think about the infirmity

that causes all other infirmities? Do we think about our sin? If we’re being honest, more often than not, the answer is no. Our aches and pains are on our mind, but not our sin.

In our Gospel reading,

we hear about the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. After John had been arrested, because he spoke out against

King Herod’s sin, Jesus appeared on the scene and continued to preach the message that John preached,

“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt 4:17).

Jesus called His first

disciples:

Peter, Andrew, James, and John. These fishermen dropped their nets and

followed Christ to become “fishers of men.” And then Jesus went

throughout the region teaching and proclaiming the gospel. He

healed all sorts of diseases and afflictions. It was this healing ministry that made

Him

famous.

News

quickly spread about a miracle healer in Galilee and people from all

over brought the sick, those afflicted with disease and chronic pain,

those oppressed by demons. Epileptics and paralytics were carried before Him. These people had no hope

before. The ailments of their bodies were a fact of life that could never be changed.

But now, now there

was hope. Now, someone was there who could alleviate their suffering,

and they went to great lengths to come to Him. People from all over

followed Jesus because they wanted to be healed and they wanted to see

healings…and

so do we. We want Jesus to heal us.

We

want Christ to alleviate all our physical sufferings. We want Him to

heal all our diseases, our sniffles, our everyday aches and pains, our

chronic pain, our cancers and heart disease, our terminal illnesses;

whatever it is, we want Jesus to cure it, to make it all go away. We

want Him to be that miracle healer for us. That’s

what we pray for.

Think about your personal prayers. When do you pray to God the most?

What do you ask God for the most? We come to

Him when we’re physically suffering, and we want Him to take that suffering away. We

come to Him at the doctor’s office and in the hospital room. We pray for negative test results and miraculous recoveries. Look at our church’s

prayer list. Who do we pray for and why? We pray for the sick, for those who’ve just

received a serious diagnosis, for those who are suffering physical ailments. We pray for recovery, for healing.

Now, before you begin to think that I’m suggesting we shouldn’t

do this, I’m not. It’s good and right for us to come before God with cares and concerns. It’s

good and right to pray for our brothers and sisters in Christ who are ill. It’s good

and right to call upon God for help in our time of sickness and need. This is a sign of faith,

and God wants us to do this. But

too often we do this without recognizing what our true need is. Yes, we’re

need physically healing, but more than that, we need the healing of our sin.

The physical infirmities we have, our chronic sickness, our life threatening diseases, they’re only a symptom

of our true problem. The true problem is our sin. Our sin is the cause of all of this. I’m

not saying that you get sick and have aches and pains because God is punishing you for a specific sin that you’ve committed. No, that’s not what

God does. But our sin, your sin, my sin, it’s the cause of sickness because sin destroys God’s creation. Sin ruins the life God made for us.

This happened all the way back in the Garden when Adam and Eve

chose to reject God and instead did what they wanted to do. That’s what sin is. Sin is a rejection of God. Your sin is a rejection of God.

It’s a turning

inward on yourself, and the result of this rejection is brokenness.

The result of this rejection is separation from God and His life. The

result of this rejection is death, and so that’s

what you suffer.

Your ailments and illness, it’s the sign of

your death. You need to realize this and repent of your sin.

Remember the message that Jesus proclaimed,

“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.”

When you suffer sickness and disease, you need to repent, because it’s a sign of your sin. When you endure

the everyday aches of life, you need to repent, because it’s a sign of your sin. When you mourn the death of a loved one, you need to repent, because it’s

a sign of your sin. When you see death in your life, you

need to repent, because you’re a sinner, and you need the true healing that only Christ can give. This

is why Jesus came.

Jesus is the Great Physician that heals that which truly afflicts you. Jesus didn’t

come to be a miracle healer that’s

only concerned with your physical problems. Jesus is the miracle

healer that cures you of your sin and death, and He does it with the

medicine

of His Body and Blood.

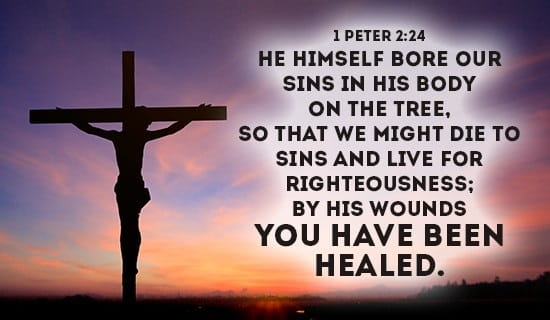

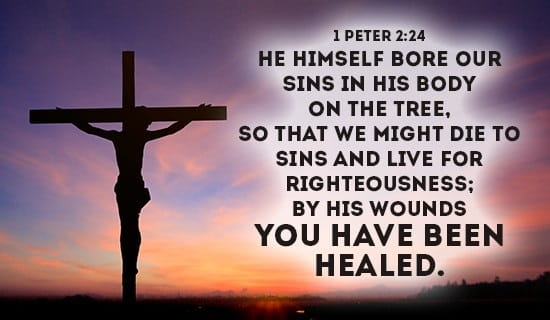

Christ heals your sin, He cures your death with His death. The forgiveness of Jesus’

cross removes the quilt of your sin, it washes it away. And this forgiveness is given to you in the miracle Lord’s Supper. That bread which is His Body and that

wine which His is Blood, it’s the medicine of immortality. It takes your sin and death away and it gives

you everlasting life. It takes care of your true infirmity so that everything else you suffer can’t harm you. Does this mean you’ll

never get sick again? Does this mean you’ll be healed of all diseases? No. But it does mean you can

endure your physical infirmities by the strength of Christ who died for you. It

means that you have everlasting life, and no sickness or disease, no death can take that way.

Like

the people who came to Jesus in the Gospel, we seek Him wanting Him to

do away with all that plague us. We come to Him in prayer, pleading

for relief. And this is good, for He is the Great Physician. But He’s the Great Physician not because He only heals our bodies. He’s

the Great Physician because He cures us of our sin. His message is

“Repent,” and when we come to Him in repentance we receive the

forgiveness that cures, the forgiveness that gives you

everlasting life. In Jesus’ name...Amen.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/50023137/shutterstock_148458620.0.jpg)