A few decades ago, when the worship wars were really pitching books and essays like cannon fodder at the other side, David Luecke introduced into our Lutheran distinctions style versus substance. What was notable about this 1988 book, Evangelical Style and Lutheran Substance, was that it was published by Concordia, the official source of theology in print for the Missouri Synod. Books published by CPH must go through doctrinal review and, while they don't officially speak for Missouri, they have the imprimatur of the Synod on them. It was a book that was clearly the mouthpiece for a certain portion of Missouri that reached its peak during the Kieschnick years and has since been demoted from its once prominent position.

I certainly do not have the time or the inclination (and you do not have the attention span) to rehearse the full story of those worship wars right down to the present day. However, it is noteworthy that the evangelical style of Luecke was not only an appeal to adiaphora (a distinctly Lutheran word for things neither commanded nor forbidden by Scripture and therefore which cannot be used to bind the conscience). It was also the official introduction to our circles of the idea long floating around Rome and other theological centers that a great amount of what we think and do as Christians is born less of faith than it is culture. Indeed, Luecke and others complained that Missouri was not just too rooted in one time but also too German. Hidden in a discussion of village and camp, evangelism and marketing, style and substance, was a judgment that we were too bound by cultural things and that these cultural adiaphora were preventing us from exploding on the Christian scene with the good substance (theology) that Lutherans had. In other words, we were being held prisoner by our culture (and the adiaphora forms and rituals of worship to which we were too attached).

Most the arguments against Luecke were based on his reading of the Lutheran Confessions -- his misunderstanding of what adiaphora actually means and his misapplication of that term to things which are non-negotiable with culture. Others complained that he was merely substituting one culture for another and one that was distinctly less Lutheran than what it was replacing. Others wondered if maybe we were too German, too liturgical (like that had ever really been a problem in modern day Missouri), or, perhaps, even too Lutheran.

No less than Peter Berger has suggested that for Lutheranism, ethnicity is no longer a real distinguishing factor in America. Berger writes a brief history of Lutheranism's journey to America, its growth in America, and the resulting drop of the Umlaut (the little dots above some vowels in German). The dropping of the Umlaut is Berger's expression for the stripping away of much of the once defining culture of German, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Danish, etc... Lutherans and their resulting separate Lutherans jurisdictions in the new found homeland. For Berger, Lutherans of all stripes have pretty much cast off nearly every restraint of culture and ethnicity.

While we in Missouri might be on the end of the wave, his words are worth pondering. Have we too quickly demurred to our German-ness to blame for things that have nothing whatsoever to do with culture and ethnicity? Have we been labeling as German things which are not at all representative of our German (or any other) culture and ethnicity? In his comparison to the often strident and rigid divisions of culture and ethnicity among the Orthodox in America, Lutherans come out pretty well (if viewing your cultural and ethnic heritage as legacy more than identity is good). In fact the truth is that even Rome sees the old divisions fading -- both by the organized effort at consolidating parishes and by the overall loss of ethnicity as a central component to individual and family identity.

Where I live, in the new South on the border of Tennessee and Kentucky, minutes from Nashville, the place were culture continues to dominate is Sunday morning and the great divide between predominantly white and Black churches. When I moved here a couple of decades ago I was told bluntly by a prominent Black pastor that if any Black folks came to my church, I should send them to him. He was not speaking as one who advocated a racial divide -- far from it -- but as one intent upon preserving the Black culture -- of which church was a very significant component. I do not believe that too much has changed in this city on that point.

To finally bring this to an end, what I am saying is that it is a quick and easy thing to lay blame on things that have prevented churches from growing and flourishing. It was too quick and too easy to lump together real cultural and ethnic barriers with such things as liturgy and hymnody. It was a too quick and easy presumption that if we could just cast off our German-ness, trust one another to experiment carefully, and allow the boundaries of our identity to be enlarged, we would harness the secret of evangelical style and Lutheran substance and take America by storm. We were confusing ourselves. Style is substance in many ways and substance is nothing without the resulting practices (style) that manifest what is believed in the life of the people gathered to worship, pray, witness, and serve.

We were too hard on ourselves. We Lutherans in the Missouri Synod long ago stopped being German -- long before Anheuser-Busch gave up its German ghost and American ownership. There is no going back. Sure, we can sing a stanza or two of Silent Night in German if we want but the culture and ethnicity that once defined us has become a memory. This is not a battle against an ethnicity or a culture but with what it means to be Lutheran. The answer will not come in finding peace with American culture (like the ELCA has done) or hiding from it (like WELS) but engaging it with the steadfast and unchanging voice of Scripture, the clear confessional witness of Lutheranism, and the vibrant sacramental and liturgical worship that practices both of the above. I am always hopeful this is what Missouri wants to do and to be but that is a battle every generation wages -- at least until Christ comes again in His glory to render all of this moot.

7 comments:

Dear Pastor Peters,

Excellent blog post, as always!

I can explain a little about your comment on the doctrinal review process for Luecke's book in 1988. The president of synod appoints, on his own authority, the doctrinal review committee and they appoint the doctrinal reviewers. So this is one place where the LC-MS president has direct oversight, without interference or negotiations with others.

In 1988 it was toward the end of the Bohlmann administration years. Pres. Bohlmann had served 1981-92, so it was his doctrinal reviewers who approved Luecke's book--which book had numerous doctrinal, historical, and simply logical problems.

I may have run into one of those same doctrinal reviewers while I was Director at CHI. An article for the CHIQ came in that was critical of Luecke's book. Although that was not the main subject, the author pointed out a number of areas where Luecke was just wrong historically, and the author had the clear and incontestable proof of it, e.g, in the first constitution of the LC-MS.

The doctrinal reviewer--who had been appointed by Pres. Kieschnick--refused to let it pass, because he/she disagreed with the historical claims. I went back to the author and asked what I should do, since there is a process for appeal. The author said to drop it--he didn't want a fight, so I did. The article was never published, to my knowledge.

So basically, the people who have bought into the Luecke argument refuse to accept the clear and uncontestable history of our synod and Lutherans in America. They want to make up their own history to justify their errors.

This is one reason why it is important to get a solid-confessional-conservative Lutheran theologian in as president of the LC-MS.

Yours in Christ, Martin R. Noland

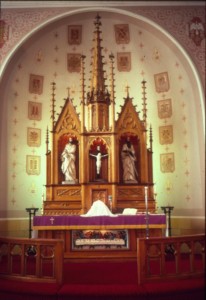

I know that church in the picture! It's the church where I serve, First Bethlehem Lutheran Church in Chicago. I think it's an appropriate picture for the post, since it's hardly one of those places that Luecke would like. The fact that we were the first Lutheran congregation to have services in sign language (back in 1894) and that we offered Spanish services for several years and that our congregation reflects the ethnic diversity of our neighborhood would not impress him. He would focus instead on the fact that our old hand-painted hymn boards (just off the picture) still say "Ger." and "Eng.," even though we don't use those boards and to take them down would leave a discolored square on the wall. (Nobody for the past 40 years or more has wanted to change the hymns on the boards every week, so we just rely on the bulletin instead.)

I'm curious, Pastor Peters. Where did you come across our picture?

Possibly here -

http://fblcchicago.org/http://fblcchicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/Photo1.jpg

I agree that the picture originally came from our church's website. After all, I took it and uploaded it onto the site. But I was wondering if Pastor Peters found it on some online picture aggregator.

substance has a style all its own.

I looked at Peter Berger's article and, although I appreciate his thesis that Lutheranism isn't as ethnic as it once was, his article is rife with errors:

It wasn't Henry Melchior Muhlenberg who had the uniform under his clergy robe, but his son Peter Muhlenberg.

Concordia Theological Seminary is not the flagship seminary of the Missouri Synod (alas!), but rather Concordia Seminary in St. Louis is.

The Wisconsin Synod has never had a seminary in Kenosha. Instead its seminary is currently in Mequon, although it used to be located in Wauwatosa. It was Wauwatosa theology, not Kenosha theology, that left its mark on the Wisconsin Synod.

Post a Comment