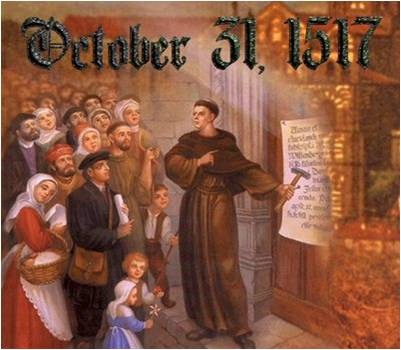

501 years ago this week, a monk teaching at a fledgling university in Wittenberg had come to believe that a personal experience of God was more important than church tradition. . . or so it was said by one commentator this week. But as surely as this is the popular reading of history, it is most assuredly a misreading of history and a rash judgment against a man who would not presume experience a pivotal magisterial role. As neat and tidy as this explanation of Luther and the Reformation might be, it is so far from the truth as to perpetuate a great and damaging lie about Luther -- but more importantly about Lutheranism -- that continues to this day.

It was a time of question and concern. What was the right and true authority for the Christian? Was it deposited in earthly men and earthly institutions or was it retained by God in the primacy of His Word as source and norm of all doctrine? Authority seems a quaint concern in our modern era in which little is granted much authority and skepticism is the norm. But Luther was no skeptic. He was not the humanist of Erasmus but a child of his time, surveying the corrupt landscape of Christianity and seeking to know that God was still present amid immoral popes, bishops, and priests, and dogmas which had no authority beyond the realms of the church which perpetuated those dogmas. He was a man with a personal stake in this crisis but he was not driven by his own experience nor was he satisfied by that experience. It was an external and objective truth He sought and it was the spark of the Reformation fire that this truth was found objective and concrete in the living words of the Word of God that endures forever. Luther could be accused of being naive and idealistic but it would be a very hard stretch to say that Luther was an experiential Christian. He certainly had little idea of the realities of the world beyond his own little world of Wittenberg nor any appreciation for the complexities of the then modern political life -- nor did he much care. There was a higher calling and a higher purpose at work in Luther and that was the Kingdom of God and how it comes. Luther was painfully transparent, moody, and filled with angst and a most unlikely candidate to have fostered the Great Reformation movement. Erasmus was surely the better choice for the role -- if anyone were casting it. But it was Luther who drove home the point over and over again and for which Lutherans still wrestle -- my conscience is captive to the Word of God. Luther was loathe to change much more in that church tradition that must be changed and then only those traditions with recent pedigree and those which promoted an anti-Scriptural accretion of works righteousness into a gracious construction of hope in Christ alone. And so we struggle with the man and the movement even today. Consider the rash of books good and bad published for the movement's 500th anniversary year. Consider the blame of some who place all modern day woes of Christianity upon the doorstep of Martin and Katie. Consider the abandonment of Lutherans of their Luther and, even more significantly, of their own Symbols. No, Luther was not an experientialist who judged tradition according to his own measure of things but a rather unlikely choice for God to use to raise Scripture up at a time when reason, works, and morality had all but buried the prize born of suffering and the life that rose from the ashes of death. Happy Reformation!

It is easy to dispel the myths about Luther cherished in non-Lutheran circles simply by pointing out what he believed about the Lord's Supper as explained in his Small Catechism.

ReplyDeleteMany Calvinists and Reformed/Evangelicals love Luther right up to the point that he gets all "Lutheran."

Sadly, even those who use his name no longer can bring themselves to confess the truth about the Sacrament of the Altar, and sadly more is the reality that even those who claim to be "confessional Lutherans" get the heebie-jeebies when they read Luther's statement, and feel a need to rush to qualify it.

"Of the Sacrament of the Altar we hold that bread and wine in the Supper are the true body and blood of Christ, and are given and received not only by the godly, but also by wicked Christians."

SA III.VI.1

P.T.McCain

"sadly more is the reality that even those who claim to be "confessional Lutherans" get the heebie-jeebies when they read Luther's statement, and feel a need to rush to qualify it."

ReplyDeleteYou do realize that this is exactly what the Formula of Concord does?

By asking such a question Anonymous on October 31, 2018 at 9:29 AM identifies himself as NOT What is a Lutheran.

ReplyDeleteQualify: intransitive verb. To restrict in meaning.

ReplyDeleteFC SD VII qualifies in what manner Lutherans confess, "The bread is the body of Christ."

"And although they believe in no transubstantiation, that is, an essential transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, nor hold that the body and blood of Christ are included in the bread localiter, that is, locally, or are otherwise permanently united therewith apart from the use of the Sacrament, yet they concede that through the sacramental union the bread is the body of Christ, etc. [that when the bread is offered, the body of Christ is at the same time present, and is truly tendered]"

Qualifies? No.

ReplyDeleteExplains? Yes.

Elaborates? Yes.