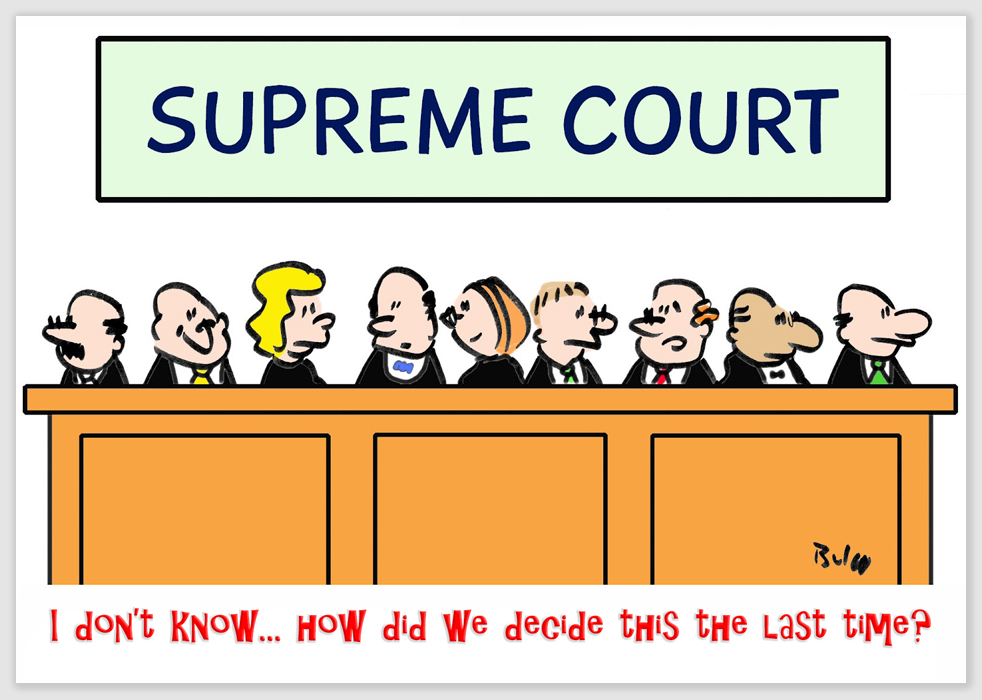

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857) People of African descent that are slaves or were slaves and subsequently freed, along with their descendants, cannot be United States citizens. Consequently, they cannot sue in federal court. Additionally, slavery cannot be prohibited in U.S. territories before they are admitted to the Union as doing so would violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. After the Civil War, this decision was voided by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.If stare decisis (Latin for “to stand by things decided”) were to determine where we are with respect to race, we would still be living in the shadow of the Dred Scott decision. This legal deference to precedent has become one of the sacred doctrines of law. Courts cite to stare decisis when an issue has already been decided by the court and the court stands by its ruling. According to the Supreme Court, stare decisis “promotes the evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles, fosters reliance on judicial decisions, and contributes to the actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process.” The Supreme Court itself usually defers to its own previously rendered decisions -- even if the soundness of the decision is in doubt. The justification for this is that the benefit of this rigidity or continuity means that we are relieved of continuously reevaluating the legal underpinnings of past decisions and what have become accepted doctrines. Proponents of stare decisis argue that the predictability afforded by this legal doctrine helps clarify constitutional rights for the public.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) Segregated facilities for blacks and whites are constitutional under the doctrine of separate but equal, which holds for close to 60 years (overruled by Brown v. Board of Education (1954)).

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) Segregated schools in the states are unconstitutional because they violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court found that the separate but equal doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) "has no place in the field of public education".

So a few weeks ago, the SCOTUS rendered a decision on a Louisiana abortion law and the decision had less to do with the law itself than it did to the issue of stare decisis. The Chief Justice, on the losing side when the SCOTUS ruled on a similar Texas law, said simply: The Louisiana law imposes a burden on access to abortion just as severe as that imposed by the Texas law, for the same reasons. Therefore Louisiana’s law cannot stand under our precedents.

In other words, we made a wrong decision then but it was the decision we made so now we must stick to it. Why would that not work in the cause of ending racial discrimination but remains the final hurdle in the Court reversing its most flawed and inventive decision in Roe v Wade? I wish I had an answer to that question. I hope and pray that eventually (will we have to wait 100 years!) the Court will figure out that Roe v Wade was wrong decision in 1973 and has been wrong ever since. Until then, as did the Dred Scott decision, our nation will live with the dispute, conflict, and division that has characterized religion, politics, and society ever since. At some point in time we hope and pray that there will be people with enough to courage to admit this wrong decision and to admit that stare decisis has caused only more blood and bitterness across America in the wake of that wrong decision. How can we fight for the rights of a few while tens of millions were and are routinely killed in the wake of a misguided and invented ruling that bypassed all political processes and turned the court into a legislative body? I wish I knew. But things are not improving on this front.

At this point, we probably need a Constitutional Amendment that vacates the Roe vs. Wade decision. If Legislatures of two thirds of the several States would call a Constitutional Convention and bring forth an amendment that 3/4 of those legislatures would have to approve. All this means, a lot more hearts and minds need to be changed.

ReplyDelete