"In what sense are our churches really and truly houses of God? We can desire nothing more beautiful and greater for our houses of God

than that they be places where the Holy Supper is celebrated according

to the institution of Christ, and a believing congregation is gathered

about the altar to receive the true body and the true blood of our Lord.

Only then will the church of the Gospel, the church of the pure

doctrine remain among us. Only then will it remain, but it will truly

remain, 'and the gates of hell shall not overpower her' [Matt 16:18].

And everywhere a congregation is gathered about her altar in deep faith

in the one who is her Lord and her Head because he is her Redeemer,

where she sings the Kyrie and the Gloria and lifts her heart to heaven

and with all angels and archangels and the entire company of heaven

sings, 'Holy, holy, holy' to the Triune God--there will her church be a

true house of God, a place of the real presence of Christ in the midst

of a boisterous and unholy world. And this text will apply to her: 'The

LORD is in his temple! Let all the world be silent before him!' [Hab

2:20]."

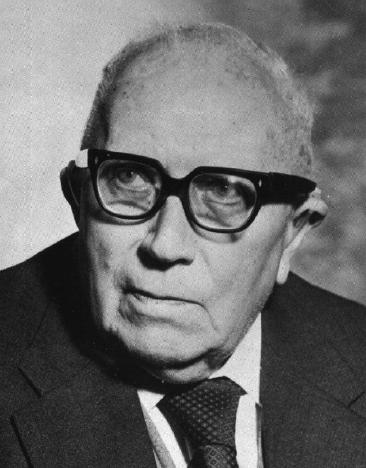

Hermann Sasse, "The Holy Supper and the Future of Our Church," in The Lonely Way, vol. 1, pp. 487-88.

Over and against Rome, Luther fought to keep the Sacrament a pure sacrament or gift and blessing bestowed upon us by the fulfillment of Christ's command to eat and drink in remembrance of Him and receive forgiveness, life, and salvation in the communion of His body and blood. Over against Geneva Luther fought to keep Christ in the Sacrament and not limited to feeling or memory but the corporeal presence of the crucified and risen flesh and blood mysteriously but really present in and with the bread and wine as His Word promises.

For Rome the Word was an appendage to the Supper and for Geneva it was the Supper that was an appendage to the Word. No church can remain true to the Word of Christ and continue to possess the saving truth without the Sacraments. Reduced to a mere spiritual fellowship of mind and heart, the church has no real point of access to the Christ who comes to bestow His gifts -- especially when the heart and mind are distracted or overwhelmed with the cares and troubles of this mortal life. When the Word is reduced to mere record of events as if it spoke about but does not bestow that which is promises, the very Sacraments themselves are called into question for it is and has always been Christ's water and Christ's bread and wine, set apart by His Word and made into the means of grace by the application of that Word to the element.

The Lutheranism of the Reformation era and the post-Reformation era -- even through the time of Bach -- knew this. But when Pietism and Rationalism had finished with us, the Sacrament was dying. Sasse recounts how from 1701-17-10 some 196,526 people had communed in Goerlitz but by the end of that century the number had declined by 100,000. What would Luther say? A church without the Sacrament as its source and summit is not much better off than one in which the Sacrament had been replaced by sacrifice and the act of being a spectator for the offering of Christ the equivalent of a communicant.

Into this era Lutheranism in America came into being. When in 1839 the Saxons came to America and got a first hand look at a Lutheranism in which the Sacrament of the Altar was absent on Sunday morning and got to know Lutheran people for whom Holy Communion was more novelty than central to their piety and life as Christian people under the Augsburg Confession. They were immediately accused of being Romanizing. With their catholic liturgy, vestments, ceremonies, private confession, devotion to the great Lutheran chorales, and their radical sacramental piety, these fore bearers of the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod stuck out like a sore thumb among the Protestantized Lutherans already here. But instead of being scandalized by their distinctiveness, they called the Lutherans present in America to task for abandoning their very identity. What was once held with bold conviction has, we are sad to say, become our Achilles' heel. We are not sure we want to stick out, to risk being called Romish, or to be true to our Confessional identity -- if doing so means we are out of step with the mainstream of American style Christianity. Perhaps the only thing that will force us to choose is the prospect of the government no longer tolerating a Christianity which is orthodox and faithful.

"Where the Supper is no longer celebrated, there faith in the Son of God as the Lamb of God who consequently bore your sins dies. And where this faith dies, the church also dies. There her profound, blessed mystery is no longer understood..." When this happens, the church becomes a philosophical fellowship wherein the religious man finds his spiritual needs satisfied and, if he discovers other fellowships that appear to do this better, he leaves the church in pursuit of his needs being met. This is not the Church that St. Paul called the body of Christ in which Jesus Christ, both High Priest and sacrificial Lamb of God gives us His body and blood to eat and drink, where we were incorporated into Him and into His death and resurrection in Holy Baptism, and where the Spirit works to sustain the faith of the baptized through the means of grace. "Behold there the tabernacle of God is among men" [Rev. 21:3]. Though hidden in the means of grace, what God has prepared for our future is already present here in the Word of God and the Sacraments of God. What we have already is the glimpse and deposit of the not yet fully revealed of what God has prepared for those who love Him.

1 comment:

"When in 1839 the Saxons came to America and got a first hand look at a Lutheranism in which the Sacrament of the Altar was absent on Sunday morning and got to know Lutheran people for whom Holy Communion was more novelty than central to their piety and life as Christian people under the Augsburg Confession. They were immediately accused of being Romanizing."

Is there a reference to being "immediately accused of being Romanizing"?

The Missouri Saxons' arrival and interactions with the population of St. Louis is described by Walter O. Forster (Zion on the Mississippi, CPH, 1953, 305-351) and in an1839 book, Die Schicksale und Abenteuer der aus Sachsen nach Amerika ausgewanderten Stephanianer (The Destinies and Adventures of the Stephanists who emigrated from Saxony to America), written by Gotthold Guenther (brother to Louise Guenther, one of Martin Stephan's concubines). Guenther included a number of articles and letters published in the St. Louis German newspaper, Anzeiger des Westens. Most of the attacks were against Stephan and his pompous behavior against the poor Saxon immigrants. Stephan's behavior had already been publicized from German newspapers while Stephan and the Saxons were still in Germany.

See also an August 8, 2011, comment regarding another claim about the Missouri Saxons and Lutheran churches in St. Louis.

Post a Comment