Church and communion

A couple of months ago [FL August 2022], I wrote in these pages about our new parochial school principal, a Roman Catholic, who had concerns that his not taking communion in our services would offend people. (I should note he was talking about the Catholic policy against it, not our policy against it.) The article detailed how I explained the situation to our congregation, which included explaining how examination for Holy Communion involved a mediating role of the teaching authority of the Church. One reader objected to that idea, asking, “One should examine him/herself in the light of the Scriptures. But why should ‘the Church’—and here I believe you mean ‘Synod’— become a mediator in this process?” The following is adapted from my response to that reader.

When I say that “the Church” has a mediating role in how we examine ourselves for Holy Communion, I’m applying the Small Catechism explanation of the Third Commandment. We all agree that we all have a responsibility to hold preaching sacred and to gladly hear and learn it. The disagreement begins when we ask, “What preaching? Whose preaching?” The catechism and the commandment from God can’t possibly refer to just anybody’s preaching of anything. God warns us repeatedly against false prophets and false preachers and teachers. If we are to hold sacred every sermon on AM radio, every pamphlet we get in the airport, every crackpot standing on the street corner explaining Revelation in terms of politics, or even every pastor in every pulpit in town, we’ll all be driven batty within a week.

Knowing what preaching to hold sacred is where the Augsburg Confession [AC] comes in. C XIV says that nobody ought to be preaching or teaching in the church without a regular call. The called and ordained servant of the Word—that is whose preaching to hold sacred. Sure, you can hear the Gospel from a neighbor or your grandmother. And yes, the condemnation of the Law can come from many quarters, too. Even the AM radio sermon makes an occasional profound point worth taking to heart. But we are also free to disagree or ignore such preaching and teaching without violating the Third Commandment. Not so the kind of preaching AC XIV addresses. The preaching the Third Commandment demands that we gladly hear and learn is that preaching done by the one authorized to preach.

But AC XIV just begs the question: regularly called or authorized by whom? Everyone who preaches claims to be authorized by God through someone or something, if only their own sense of mission. And even setting aside self-appointed preachers, every pulpit in town is filled by someone whom that congregation (or its overseers) put in place to preach and teach. Granted, we all might hear and learn edifying things from non-Lutheran pastors. Most of us do so quite regularly. But does the Third Commandment demand that you hold sacred and gladly hear and learn the preaching of every preacher in town? The Seventh-day Adventist railing against Sunday services? The Evangelical calling people to be re-baptized, for real this time? Of course not.

AC VII preempts the question begged by AC XIV. It does so by defining the Church, the calling entity from which the actual preachers behind the preaching in AC XIV get their authority, as “the congregation of saints, in which the Gospel is rightly taught and the Sacraments are rightly administered.” Wherever that is, there is where the Third Commandment directs us to hear the Word. We are not free to deny or contradict such preaching; doing so is despising preaching and God’s Word and a violation of the Third Commandment.

A positive description of the relationship between AC VII and AC XIV would be “symbiotic.” A negative description would be “circular.” And granted, it is circular to define the right church as the place where authoritative preaching takes place and then define authoritative preaching as the kind that comes from the right church. There is a chicken/egg conundrum to deciding what church to join. You join the church that teaches the truth, but learn what the truth is from the church. That’s a tough nut to crack, and only the Holy Spirit can take a person from outside to inside that circular, symbiotic process.

But the Spirit does it, when it happens, by getting you to recognize the voice of your Lord and Shepherd somewhere. That voice has to take some kind of this-worldly form, but it speaks from above you with divine authority to judge and condemn and to pardon, forgive, and sanctify. Even with the Spirit’s help, you haven’t really joined a church until you’ve placed yourself under, not over, the preaching and teaching that goes on there in the name of your Lord.

The individual preacher may make mistakes now and then or not have an appealing personality. Even the great prophets and apostles were sinners. At issue is whether the preacher’s call comes through a congregation of the saints in which the Gospel is rightly taught and the Sacraments rightly administered. If it does, you must hold that preaching sacred and gladly hear and learn it. If it doesn’t, you are free to consider that preaching for what it is worth, be it gold or tin. It is up to the congregation to insist that its pastor’s preaching not transgress the confessional bounds of God’s Word, which is why Lutheran congregations all have an unalterable confession of faith to which they publicly bind their preachers at installation.

So far, so good. Congregations with a sound, orthodox confession of faith call preachers, and the Third Commandment tells Christians to heed their preaching. There may be more than one place in town where the Gospel is rightly taught, but the preachers in those places may not contradict each other from the pulpit any more than two pastors called to the same congregation are free to contradict each other from the pulpit. The congregation’s confession of faith does not contradict itself. If pastors contradict each other, one of them has strayed from the public vow he made at his installation. The hearer cannot examine himself meaningfully according to the teaching of both of them.

Of course, AC VII refers to the Gospel in the wide sense of the full counsel of God. Preaching, according to St. Paul, includes correcting, rebuking, and admonishing along with encouraging and comforting. The Third Commandment calls us to pay heed to both Law and Gospel. God calls us to be formed by all of it, not just the parts we enjoy. Especially on the matter of our confessing actual, real world, concrete sins and not just mentally assenting to the doctrine of original sin, it makes a big difference what God’s Word says is sinful when it comes to preparing for Holy Communion.

The nature of the Church, the nature of the call to preach, and the divine command to hold preaching sacred come together in how one prepares for the Sacrament. The Word and Sacrament cannot be divided. They are forms of the same thing—Christ. Divine Service rightly brings them together. It is the preaching and teaching of the Service of the Word by which one repents of sin and examines oneself for the Service of the Sacrament. The “called and ordained servant of the Word” has authorization to forgive our sins, to preach and teach with the force of the Third Commandment, and to consecrate the elements on behalf of the congregation where the Gospel is rightly preached and the Sacraments rightly administered. Such authorization comes as a package deal.

What I wrote in my original article that merited strong objection was, “It makes no sense to examine yourself if you do not accept correction of your faith and life from anyone but yourself, and such correction can only come from a mediating authority between you and God. God doesn’t deal with you directly, but through the Church, through Word and Sacraments.” I think this is an important point. Going forward for communion is not an isolated act detachable from Christian formation and self-examination. Meaningful self-examination requires being formed by preaching and teaching, which stems from the authority of a congregation where the Gospel is rightly taught and the Sacraments rightly administered. In short, when you receive communion, you are (among other, more important things) publicly identifying the church whose preaching you hold sacred and gladly hear and learn. You are claiming to have examined yourself according to that church’s teaching.

I think the historical practice of every sacramental church body has included limiting communion (in normal circumstances) to those who accept the teaching authority of that church body. In the case of Lutheran churches not in fellowship with each other, the issue goes far beyond denominational loyalty or arrangement of the letters in the label. The ELCA and the LCMS do not offer the same “answers in the back of the book,” so to speak, for the self-test. The difference is doctrinal, not merely organizational. We teach different things about how the commandments apply to our thoughts, words, and deeds. To commune in both places is to make a mockery of the teaching authority of one of those places, or worse, to claim the right to be your own teaching authority who sits in judgment over both places, which renders self-examination a pointless exercise.

Consider the section on the Office of the Keys in some editions of the catechism. The LCMS’s Concordia Publishing House editions note that these questions may not have been written by Luther, but they reflect his teaching and were included in editions of Luther’s catechism in his lifetime. One question relates to John 20.22—23, where Jesus gives the disciples the authority to forgive sins, and the next question asks, “What do you believe according to these words?” The answer says, “I believe that when the called ministers of Christ deal with us by His divine command, in particular when they exclude openly unrepentant sinners from the Christian congregation and absolve those who repent of their sins and want to do better, that this is just as valid and certain, even in heaven, as if Christ our dear Lord dealt with us Himself.”

Clearly, what is needed is recognition of God-given authority that is valid even in heaven. That authority especially includes calling people to account for their sins and withholding the Gospel from the unrepentant. The issue is not whether we consider all non-Lutherans to be unrepentant sinners. The issue is whether they are formed by our preaching and teaching.

The ELCA solves the conundrum by saying it doesn’t matter for communion fellowship if various preachers contradict each other. Communion fellowship only requires agreement on a few key points, and even those points don’t really matter much, if at all. That does indeed solve a lot of practical pastoral problems, but at the expense of undermining any confidence anyone can have that they’re hearing God’s Word rather than tentative human opinions. The LCMS (I would say properly) requires doctrinal agreement among preachers and teachers and actually tries to enforce it. But we do end up, then, sometimes fighting with each other or awkwardly explaining our policy and disappointing or offending people who want communion in a church where they do not consent to be taught and formed.

Consider, to use a timely example for 2022, abortion providers. Are they openly unrepentant sinners? What about people publicly and unapologetically having affairs? What about a couple in a homosexual marriage? If we are called to repent by a preacher whom the Third Commandment demands we listen to, but we don’t agree with his definition of sin, we can’t with any Christian integrity just find a more amenable preacher or go by our own personal definition of sin. If we do that (and I think a lot of people do), we are saying that the first preacher did not preach God’s Word or represent a congregation of the saints where the Gospel is rightly preached and taught. The sermon was just something to consider, like a newsletter article. I think many mainline Protestants think of sermons in Divine Service that way.

The attempt to have fellowship despite contradiction always ends up elevating personal, private opinion and interpretation above the teaching authority God gave the Church. In short, it makes everyone the pope of a church of one and renders the unity of communion a mere outward show.

So, the best practice: Receive communion where you accept correction of your faith and life. If you recognize the teaching authority of Rome, receive communion at Catholic Mass but not in Lutheran churches. If you are Lutheran, receive communion where you recognize the teaching authority (which cannot be both the ELCA and the LCMS since they contradict each other) but not in Roman Catholic churches. Such discipline has been recognized and practiced historically by all the sacramental churches, and it makes perfect sense. It does not really solve the ecumenical problem, or even make a phony attempt at solving it, but it does maintain the integrity of the Divine Service of Word and Sacrament for all parties engaged in that ecumenical problem.

As for ecumenism, I think it helps to recognize the nature of the problem not as disagreement on a list of specific points of doctrine that need to be addressed but disagreement on the source and nature of the authority to preach and teach in the Name of Jesus. Among Lutherans, disagreement on the nature of Scripture is what leads to division, just as among Catholics disagreement as to who is the rightful pope has led to division. It isn’t enough for Catholic unity to acknowledge papal authority if you don’t agree on who is the pope, and it isn’t enough for Lutheran unity to acknowledge sola Scriptura and the Confessions based thereon if you don’t agree on the nature of Scripture.

Our Catholic principal communes regularly. As do St. Paul’s members. He just does it about two tenths of a mile up the street from us, where he submits to the teaching authority of St. Thomas More Catholic parish. Then he comes to our services, too, and listens intently as to something interesting for him to consider. Nobody is being denied Christ by taking communion where they heed the Third Commandment and receive both Word and Sacrament.

If it matters who is kneeling next to you, it should not be because they are kin by blood or because you love them. The fact of “communing together,” as opposed to just communing, should only matter if you share the same faith. And since nobody can claim to fully understand (or in many cases even know about) every teaching of the Christian Church, the faith people who commune together share is functionally a matter of holding sacred and gladly hearing and learning the same preaching and teaching of God’s Word.

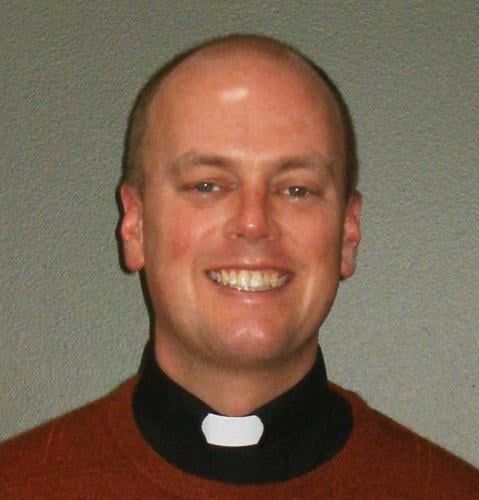

—by Peter Speckhard, associate editor

3 comments:

Wait! What?!?

"... our new [LCMS Lutheran?] parochial school principal [is] a Roman Catholic"

Does the hyper-ecumenical congregation have a Mormon as a vicar?

Obviously the Roman Catholic was not catechized well because if he/she was, then this would not have been an issue.

Both comments seem rather absurd to me. The congregation is hardly "hyper-ecumenical" for employing a principal who is Roman Catholic. The congregation has pastors assigned for the spiritual responsibilities of the school and anyone with half a wit knows how hard it is for an LCMS school to find an LCMS principal -- even a rostered teacher for that matter.

I found the man very well catechized and even concerned to know both what the environment was in which he was employed and to make clear his own religious identity without offense. If only we were so clear and concerned as Lutherans!

Post a Comment