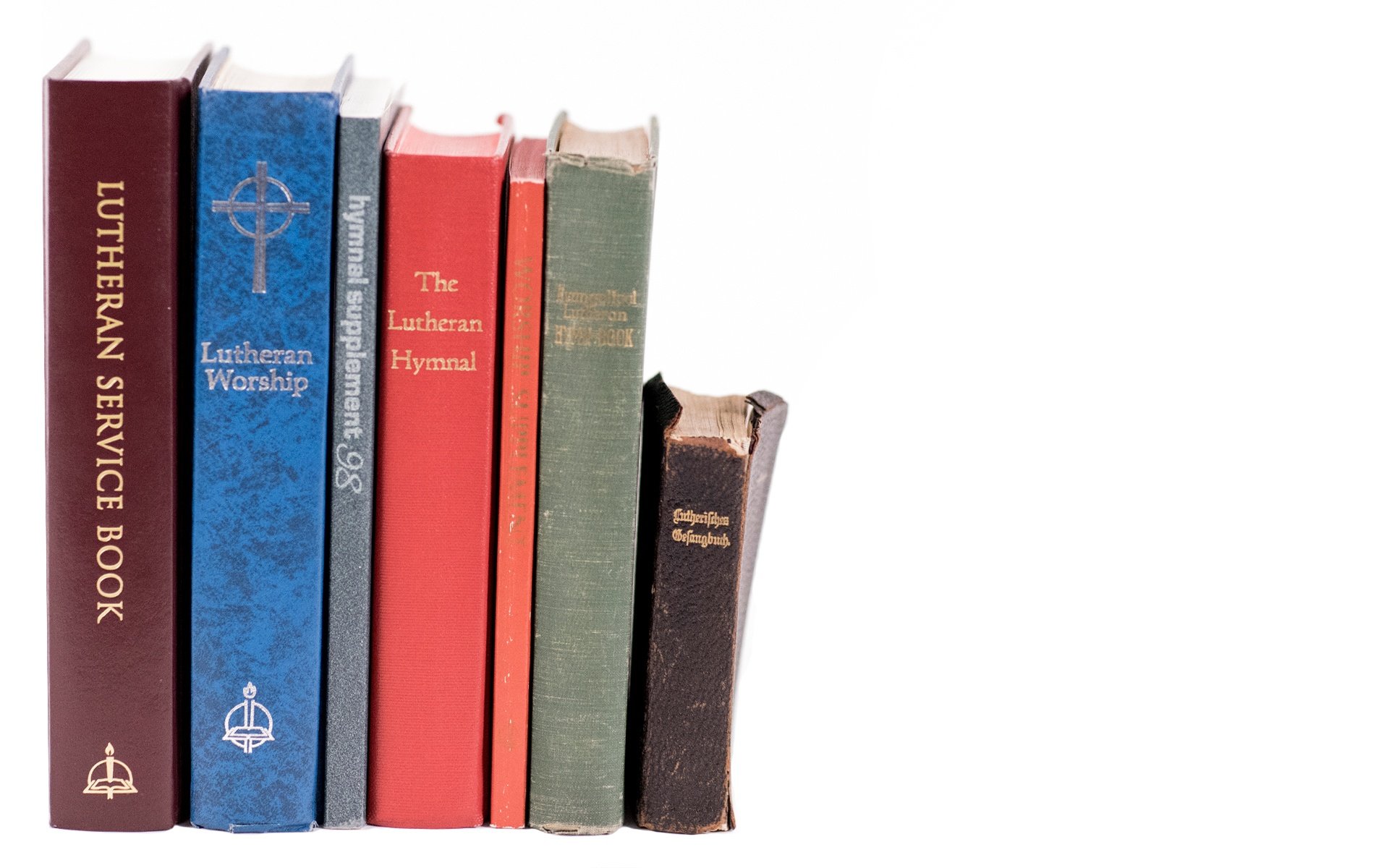

Most hymnals over the years have represented some for of restoration of what had been lost. Certainly this is true of the hymnals that have embraced the Common Service (1888) tradition. It was about more uniformity, certainly, but uniformity not from rites that had drawn too deeply from the well of tradition but rather those rites that had abandoned the distinctive marks of our liturgical identity. With each hymnal, the tradition was reclaimed and set out as that which defines the Divine Service in a minimal sense. With Lutheran Worship that changed and the adoption of the newer rites and music from the LBW tradition while editing the TLH tradition to the point where it almost became a brand new rite, things were turned around a bit. But Lutheran Service Book reclaimed that role as restorer of tradition by resetting the third setting of the Divine Service to match almost exactly that which had been received in TLH. It did so while again ordering the rites to bring more uniformity and unanimity to the worship life of the congregations of the LCMS.

It must be noted that there were attempts to restore several items to the Divine Service which did not make it into LSB. One was the Eucharistic Prayer. An example of an evangelical Eucharistic Prayer was studied and then rejected out of concern for that hymnal's eventual acceptance and because there was not unanimity within the LCMS on this issue. Another was a change in the wording of the Nicene Creed which was proposed and studied but then at the Synod convention rejected in favor of the wording from LW. In both cases, these were not attempts to advance the liturgical life of the LCMS as much as they were to restore things to the rite. The rubrics or ceremonial direction for the hymnal were adopted not separately but as part of the hymnal itself (something slightly different than the adoption of TLH). Again these rubrics and general ceremonial instructions did not delineate what must be done and no further addition but in a basic or minimalistic sense -- what was basic to the rite and to our liturgical tradition as a church body.

Before anybody jumps in with some comment about adiaphora, let it be known that the Synod has judged orthodox hymnals, liturgies, and agendas as not adiaphora but essential to the unity of the church body and part of our confession of faith. Adiaphora is general invoked as a cause or justification for omitting what we have published (in favor of something else) but it could just as easily be invoked as rationale for adding back things from our history that were not currently part of our hymnal or our liturgy. However, I am not addressing adiaphora here -- only the question of whether what was published in LSB constitutes the boundary of which we dare not pass or a minimal standard which is expected of all. Again, it is my conviction that LSB represents a minimal standard or expression of the liturgical identity that is also part of our confessional identity. That said, it does not violate the hymnal or our unity of faith to restore what was omitted over time. In fact, it is this way that the what was lost is restored, recovered, and reclaimed.

The appeal to what is Lutheran or not usually ends up somewhere in the middle, a consensus of the various liturgical patterns of the Lutheran Church Orders of the 16th Century and their development. But that is not Lutheran -- not a majority vote of how individual jurisdictions changed or reformed the liturgy. What is Lutheran remains the principles of the Augustana. No absolute uniformity is required, however, church usages, ceremonies, and rites are not subject to our whims but to the catholic principle of keeping what can be kept and only rejecting what conflicts with the Gospel. Years have passed and now the liturgy has become a personal domain of preference. Our hymnals have left us with a faithful pattern of the Lutheran liturgical average but the catholic principle of the Augsburg Confession not only allows for but actually encourages the restoration of what has been lost, the recovery of that which has fallen out of use, and the use of as much as what can be used without conflicting with the Gospel. But our eyes have narrowed today so that the Formula Missae of Luther, not a rite as much as a set of notes for the use of the Catholic Missal according to evangelical use and principles, seems foreign and alien to a community that has become more comfortable with praise bands and worship without a rite than with the rites that fit well under the Augustana norm?

So, again, my point, the liturgy of the hymnal, whatever that current hymnal is, is not nor can it be the maximal pattern for liturgical worship but remains a minimum, a basic order that is essential to the unity of our confession but to which additional ceremonies, rites, and rituals may and are encouraged to be restored within the catholic principle of the Augsburg Confession.

2 comments:

The basic tug of war between the conservative and confessional liturgical camps is essentially this: do we model our liturgical practices on the consensus of the Lutheran Church (Gerhard) or do we aspire to reclaim the liturgical ideal of an Augustana Catholicism?

If you are a conservative Lutheran, you look no further than Melanchthon, who wrote concerning the eucharistic prayer: “The controversies about the canon were of the highest importance to me, and I thank God, if I succeed in preventing that these impieties are forced on the pastors.”

If you are a confessional Lutheran, you are left casting about for isolated examples from Petri’s Mass, or King John’s Red Book, or Agricola’s defense of the canon as a prayer of thanksgiving, etc. These rather specious instances were never adopted by the Lutheran Church at large, however. And they really are not the heart of the matter. The goal rather is conformity with a catholic liturgical identity rather than a Protestant Lutheran reality, which did not simply come into corrupted being over time, but was present in the fiber of Lutheran statements on liturgical practice from Melanchthon and Chemnitz from the beginning and are furthermore part of the Book of Concord as well. When Melanchthon states in Augustana XXIV, “The Mass is retained among us,” he then goes on to state all of the different ways in which the Lutherans have changed the Mass to conform to the principles of scripture alone and justification by faith alone. When Chemnitz describes Lutheran liturgical practice in the Formula as “that in an assembly of Christians bread and wine are taken, consecrated, distributed, received, eaten, drunk, and the Lord’s death is shown forth at the same time must be observed unseparated and inviolate,” he is defining Lutheran, but not necessarily Catholic practice.

The question remains, what is our liturgical goal?

Although I agree with you final question, you have made a couple of assertions that beg to be challenged. Luther, Melancthon, and others did indeed write against the Roman Canon -- the Eucharistic Prayer they knew at the time -- but none of them wrote about a Eucharistic Prayer in general or about the possibility of an evangelical form of a Eucharistic Prayer. The assertion that they did is simply not true. They wrote against ONE Eucharistic Prayer, the one they knew with language exclusively sacrificial. Secondly, while the choice may be between a supposed consensus of forms along the way or the ideal of the Augustana, only one has the power and force of a Confession and only one binds us to anything. Liturgical theology is, in many respects, always a work of restoration since what is lost quickly comes to be called normative.

Post a Comment